1991 Part Four

| Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Five |

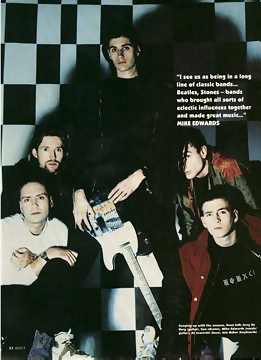

Interview - Lime Lizard magazine - circa April 1991

Things move fast in the 'real real real' world of Jesus Jones. No sooner

do their appraisers bestow upon them the impossible tag of 'great

white hope' than their detractors refer to them as 'state of

the art without the art'. Sitting upright in the spartan surrounds

of their record company offices, singer, Mike Edwards and 90s

sampler-sage Barry D remain suitably disinterested. They are

supremely self-assured, and if this is confidence that is so

often mistaken for arrogance it is merely a confidence born

from the secure knowledge that they are making soaring, bright

pop which displays an energy, vitality and genuine groove sensibility

so lacking from the indie-dance bands that threatened to obscure

them in 1990.

I tell them that I think the new album Doubt displays

more varied colour, more international culture than their debut

LP Liquidizer.

Mike: "Yeah, Liquidizer was certainly ramming home

a point, there was no arguing with it whatsoever, and because

it was so direct and straightforward and self-assured, there

was no room for doubt or any other consideration which is why

we got into such a love-hate situation with the press. Doubt

is a lot more considered; it's often very self-questioning and

it's a lot more interesting. There are a lot of different ways

into this album, whereas with Liquidizer, it just steamrollered

over you."

I ask them whether they still see themselves as the link between

house and guitars?

Mike: "Yeah, I could see there were big gaps between what

the best people in all types of music were doing. Being thrilled

by the impact you could sense house music was going to have,

the excitement of it all, and the controversiality of rap music

- all those things, were immensely exciting and the idea of

taking the best bits of them all and the best bits of great,

classic, rock bands and putting them together; that was really

the idea behind it. I don't think we were ever on a huge crusade

or we were going to be the salvation of rock music. Occasionally

we might have said things like that purely for effect, but it

was really just a case of doing it the love of music. I genuinely

liked house music and still genuinely like it. It was massively

influential on Doubt and the sort of samples we're using

often come from pirate radio stations. I do see us as a link

between those things and the indie dance thing never really

took house music on, on its own terms. It never actually faced

up to the issue of what house music was about."

Mike disputes the charge that EMF have stolen their thunder,

reiterating: "The fact is that like us or dislike us we

were doing this indie dance thing in a convincing way a year

before it became fashionable."

I mention the Luddites among their critics who seem to object

to their hyper-modern stance.

Mike: "I think if you object to someone being of their

time or ahead of their time, that's as sad as you can get. It's

the natural birthright of humanity to progress; it's the duty

of humankind to progress in any form, even if it comes down

to a silly little thing like rock music."

Barry: "I think a lot of it, as concerns criticism in the

press, is all down to the 'fuck me, I wish I'd thought of that'

factor."

Jesus Jones are a great pop singles band. Their 45's display

the sort of gleaming pop vision that they reckon The Wonder

Stuff used to possess. (Mike: "It's not to our advantage

to say so, but yeah, we're big fans.")

I ask them about their attitude towards singles.

Mike: "If your gonna release singles they should be great

pop singles. Why else bother, unless you can come up with a

classic track? That really was our thing behind Right Here,

Right Now. It was not a great pop single but it was a great

song and it was the right time to release a great song. That

realisation made releasing International Bright Young Thing

the perfect proposition for now."

Asking them about their influences gives them, or at least Barry

D (who wants to be know as Iain this year!) an excellent opportunity

to really let loose.

Mike: "At the moment I'm listening almost exclusively to

Middle Eastern folk music and house."

Barry: "Mostly I'm listening to dance music and, like I

say, anything that's white, indie and guitar orientated I loathe.

Everybody that appears that's not dance-orientated in John Peel's

festive 50. They're all wankers. I hate them all, literally.

I'd buy none of their records. I think they're all shit."

"There you are, Barry D. Always quotable," adds Mike

humourously - if somewhat nervously- at his erstwhile partner's

rantings. But Barry D hasn't finished yet: "I've read issues

of Lime Lizard before, and I should think, about 90% of the

readers, I'd like to go round and burn all their record collections."

"The problem comes," counters Mike, "when they

find out where you live and burn all your records!"

How do they then see the future and how do they envisage the

monster they've created developing? In short, they tell me that

the blending of house and rock music wasn't their only idea

and that they will continue in their efforts to change the course

of music.

"I know that sounds ludicrously grand, but I wouldn't want

anything else," states Mike.

Barry: "It's worth going for. 1990 was the year that a

lot of people tried to smother us under an immense mountain

of indie shit basically, and I think we weathered it well. We're

still here to be talking about it."

I can't help pointing out to Barry D that Jesus Jones might

just have attracted some of the very fans whose record collections

he would once have eagerly burnt.

Barry: "Yeah, in the 18 months that some people have been

following us around you can tell that after a while the Sisters

of Mercy-things on their kitbags are tippexed over and The Shamen

will appear and you think, "Hang on a minute, we are having

some sort of positive effect here."

"And that's our plan for the future, that's the way that

we'll affect people and change their opinions of rock music,"

adds Mike Edwards thoughtfully. "Before lunch."

Clipping from Music Press

Jesus Jones look set to sell out their next US tour before even arriving in the country. One week after announcing gigs in New York, Boston, Chicago and Washington DC, tickets were no longer available. In Los Angeles, where Jones fever is most prevalent, two nights at the 2,500 capacity Ackerman Ballroom have sold out more than a month in advance. The band are currently Number One on Rolling Stone's college album chart with 'Doubt'.

Review (well rant of a jealous Journo more like) of Gig at the Ackerman Ballroom, Los Angeles - probably from Sounds - circa May 1991

If selling out was an Olympic event, Jesus Jones would be gold medalists

and world record holders. It's a shocking jolt of commercial crassness

to see a band so willingly go from being a heart-fluttering fizzy pop

group to a user-friendly bunch of conceptualists in six months.

But it makes it easier to see why Jesus Jones have been clasped to America's

ample bosom and hit the US pop chart while bands like Happy Mondays

must be content with languishing on the less mainstream college chart.

Mike Edwards has the sort of poster boy good looks that will put him

on the walls of a million American Sharons. Shaun Ryder, however, has

the sort of looks that will put him on "Wanted" posters in

10,000 American police stations.

In fact, it's Jesus Jones whose mugs should be plastered on every available

wallspace, under a sign reading, "Missing: four sets of balls.

Last seen in EMI executive offices."

Interview and Gig Review - Japanese Magazine - 6th June 1991

Interview & report from June 6, 1991 show @ Shinjuku Power Station. This is in Japanese and to preserve the Japanese characters the item will open as a PDF document in a new window. Click here to see it. The photos below are from the magazine.

Interview - The Island Ear (New Jersey US Mag) - 10th June 1991

Every few years alternative music finds itself in danger of wallowing in its own pretension. America exported house music to Europe in the mid-80s and Europeans, knowing a good thing when they hear it, re-invented it (and mutated it, thus the Summer Of Love 1988) and sold it back to us. Even with this injection of new blood, club culture was getting perilously close to becoming a game of follow-the-leader as bands grabbed their predecessors' tails instead of milking the newly found youthful enthusiasm.

Jesus Jones' timely intervention reminded us that rock and roll and house music are not mutually exclusive genres. In the year that the group's albums have been available in the states, they've bulleted from the Top 10 Alternative chart to the Top 40 Pop and AOR charts. Before their recent Long Island gig, vocalist/songwriter Mike Edwards settled down backstage for an hour to talk to The Island Ear.

Does "Right Here, Right Now" mean something different in light of recent events?

It does to Americans. Last night a girl told me it gave her a great deal of help, a spiritual uplift because she had a lot of friends who were actually fighting in the Gulf and obviously she was very concerned about them. That was very touching. People are not interested in the specifics of exactly what the song is about, listening to every single word throughout the verses or whatever. The lyrics in rock aren't that important. People here seem to have taken the optimism of it, just the sentiment alone and liked it for that. The song has come at a very meaningful time for Americans. If anything it's become more relevant now than when it was released because here there is this great feeling of relief and optimism.

Last time we talked you told me you didn't enjoy making the rounds to show your face to retailers, etc. Does that still bother you?

No, it doesn't. Alan and I had a huge argument about this last night. Life is full of complexities. It isn't "do exactly what you want and you will succeed." You have to remember as well that these retailers or whatever don't want to meet you much either [laughs]. Life is like a game of chess, which is a horrendous thing to say but I'm borrowing it from this crazy person I saw in New York who came up the road screaming, "It's all a game of chess!" He's absolutely right, because it is full of complexity. You have to make small sacrifices to get what you want. In rock music I think the means really do justify the end, but you decide how much you want to compromise because compromise does come into it. But you can make the most of it and have fun. For example, those phone calls to people who've bought our record were done by all five of us in a speaker phone. It was one of the most surreal occasions ever. One poor woman, within about 20 seconds was describing her underwear to Jerry [De Borg, guitarist].

You'll compromise your time, but what about your music?

No, absolutely not. That's the one time where it isn't worth compromising because then you lose sight of everything. I wouldn't like to succeed with music I didn't like. We've only ever made one record I didn't like, the 7" remix of "Who? Where? Why?" and it's only come out in Britain. It was an interesting lesson. I actually found that although it sold well, I didn't think, 'we should do something like that again.' I actually still hate the single. It makes me even more determined to make the sort of music I like whatever the cost.

Has success reinforced the confidence you said you'd lost before writing Doubt?

Yes, it has. Just writing that album really reinforced it. It was a cathartic thing. I read a Michael Stipe interview recently where he said he believes rock music to be very cathartic. I agree that it is for the writer first and foremost, but also in a diminished form for the audience. I get a lot more confident having doubted myself and in that period of doubt found my way out of it by writing these songs. So I do feel very confident now, hopefully not insufferably confident.

You just performed in Massachusetts for Earth Day. I didn't know you were an advocate of the environment.

I'm torn about these things. It's fair enough because I do believe in the cause, but I don't want to make a big issue about it. But when you do those interviews at the show, suddenly you are. To be quite honest, it was a chance to play in front of a lot of people. I don't feel bad about it because I do believe in the cause but I prefer music being music and causes being something else.

Your songs are not totally apolitical, though.

I always try and make them socio-humanic rather than political. What interest me is the way politics affects people rather that the politics itself, the way it affects small lives or even the way everybody's lives are affected by small decisions. I steer clear of writing about politics mostly because I don't believe I have the answers. I think as soon as you start to criticize, you should be able to come up with solutions. I'm not really sure that I'd make a great politician . In fact, I'm pretty sure that I wouldn't.

There is a line in "Right Here Right Now": "Bob Dylan didn't have this to sing about." Is that a statement of how you feel about the 60s?

No, I'm not against the '60s at all. I've actually often thought about that line. I'm sure Bob Dylan did have things equally important to sing about, possibly more so if your countrymen are being shipped out to fight a war that few of them believed in or knew anything about. It's probably far more relevant than talking about things you see on the television happening a few hundred miles away. My only hang up about the '60s is that they are so vogue-ish at the moment. With all the Manchester bands just making pastiche '60s records, I'm hesitant just to think about the '60s. If anything, I have a lot of admiration for that period and for the people then because it was a time of great experimentation. When I was writing Doubt I was thinking very much about records like The White Album, which could only have been made at that time because of its very experimental approach and its very eclectic outlook. That's what I wanted to do with Doubt, to make an album that shared the same attitude as perhaps the Beatles did at that time but do so in a modern way.

In "Who? Where? Why?" you sing, "Have you ever felt that there's someone else living your life?" Did you feel you were losing control of Jesus Jones or of your life?

There have been times like that, certainly. With my lack of confidence I wasn't really sure which part of me was making decisions, whether I was making decisions instinctively or on a purely emotional basis. I didn't seem to be emotionally involved in any of the decisions and it made me wonder if I truly believed in it all anymore. Was it the real me that was in control or had I just become a nodding yes-man or even a shaking-my-head-no-man without any real reason or logic?

In "Welcome Back Victoria", you sing about a general return to conservatism. Have you been affected by censorship?

No. I've got nothing to hide with my lyrics anyway. Even if I wrote something a bit risque I'd certainly send it in for submission and fight it all the way. We haven't encountered anything like that but then, putting a poster of lots of penises in with our records, for example, is not interesting to me. Those aren't the sort of statements I want to make. I have things to say about anti-censorship but not the reasons censorship exists. The Jesus Jones attitude tends to be "live and let live." It's not a woolly liberalism but there aren't things I really feel I need to stick my neck out about. That's probably a failing on my behalf.

Would it bother you if there was an explicit lyric sticker on your records?

Yes, It would. I quite like the Bart Simpson approach which is to say "Damn right they should have these stickers so your parents know not to buy that record. It's for you, kids. Buy this record and you're automatically taking a stand against boring people." Seriously, it's a type of categorisation. I absolutely loathe and detest that. Things shouldn't be broken down into baby food. They should be rough and ready as life is.

What's the story behind "Stripped"?

I'd written the music first as I normally do and it became something very brutal and sort of unforgiving. There was no hiding behind anything with it. I wanted to write about the experiences that we'd had in Rumania, how you do feel stripped of all artifice. There was no room for pretense there whatsoever because it was so extreme. We were coming from a cushy life compared to the people we met there. It describes how we were moved to the point of almost tears of frustration about how things couldn't, or wouldn't, change, about how the revolution was stolen from the people who had died for it.

The liner notes of Doubt are more personal than on Liquidizer with the exception of "Broken Bones" where you note "I'm Mike, like me." Is Doubt a more personal album?

Yeah, it is. That note on "Broken Bones" actually was written near the time we were recording Doubt. Liquidizer was a very extrovert album. The lyrical matter on Doubt is far more introspective. It was more about me, anyway, and I was much more involved because I was producing it. It felt more like my album.

I'm obsessive about the songs. Self-producing was the way I could assure they came out the way I wanted them to. There are elements of Liquidizer's production that I didn't like, but I thought I'd learn to love. Interestingly, there are elements of Doubt that I don't like now, and I think that's important if you're going to make another record. Also because I felt very strongly about the album, because it was a cathartic album I wanted it to come out exactly the way I had imagined it, which meant I had to take all responsibility. I couldn't ever sit back.

Iain Baker, your keyboardist, has a writing credit on this album for "Nothing To Hold Me."

I asked him to do it. Again, with this album we're trying to show the band in a different light. One way of doing that is to show more of the band so I asked him to write something. I had to push him very hard actually. It took three months for him to come up with those two verses.

Are you surprised at the state of house music in its home country?

I think it's yet to really hit here. Even though we're doing a very different version - we're not making house music, we're making music that's influenced by house music - I think we're part of the wave that will introduce [it]. Technotronic having huge hits was a start as well. One of the great joys about house and rap music is that they've become very popular and a lot of it does sound so hard and so wrong for mainstream radio, but it just powers its way on there anyhow, like Public Enemy or even Technotronic. In retrospect we think of the first couple of Technotronic songs as being very poppy, very gimmicky. They sounded hard as hell the three weeks before they hit mainstream release when they were just being played on pirate radio stations. There was a time when Technotronic was as hip as you could get. I still say that house music will influence music as much here as it did at home, that it will revolutionize mainstream rock music, too.

It's the classic scenario, though, of Americans making music, exporting it to Britain and the British re-exporting it in a slightly different form. It happened with punk and I do see a very strong similarity between the two. It's the same situation in America now as in 1978 when people heard about punk and said it hadn't really happened here. Well, not yet.

Are you the Sex Pistols of dance music?

Oh, absolutely not. All those comparisons are terrible. We were watching MTV and poor old EMF, the VJ introduced them as "The Mozarts of Pop." "The Something of Something" is always a terrible thing to be.

Is there any hope for America musically speaking?

Absolutely. Any new idea if it's a good one seems to be readily taken to by Americans. America impresses me with the enthusiasm and the energy people have about new ideas. You're not weighted by tradition the same way Europeans are. [In Europe] you often feel there are lead weights around the collective feet of society. Here things are embraced and rushed away with. Possibly that's what's happening with us, being indicative of this new wave of house-influenced bands.

I have noticed that a lot of young, intelligent Americans are skeptical about their own country which I find surprising. It's similar with me. I look at new British bands and I don't find a lot that I like. I think it is a case of the grass being greener on the other side. We're coming into an age when where you come from is no longer important, it's just the bands that are important. In Europe, where we will have the United States of Europe quite soon, I think it means we're going to have a very different attitude.

What about the influence of international music?

By saying it's not important where you come from and by accepting the global village idea [as in "International Bright Young Thing"] doesn't imply that music has to be mono-cultural. Because you and I speak English doesn't mean we speak it the same way. It's the same with music. We were re-recording "Who? Where? Why?" yesterday for America and we were doing African and Indian stuff. Maybe the only advantage in coming from big cities like London or New York or Tokyo is that new ideas in any art form come through there normally sooner rather than later. But otherwise, I reject the idea that with the age of information and communication upon us where you can dip into other people's societies with great ease, it means that you're going to be mono-cultural. I think all it means is you realize how much variety there is in the world and how much you can use it.

I find it ironic that the song is also a poke at egotistical rock stars.

Because I have the capacity to be that myself?

No, because it seems to be making such a positive statement.

Because it's done in a lighthearted manner. You don't have to be dour to parody someone. Just the title alone - "International Bright Young Thing" - is quite silly. It's important when we release bright, shiny pop singles that are competing with mainstream pop artists, that there's something to make them stand out. That happens lyrically. Most importantly I meant to talk about the people I met all over the world, that I felt I was sort of representative of them or part of it all. But I also felt that just saying "We just came back from Tokyo the other day" was pretty farcical. It sounds so ludicrous that if you say it with a smile people realize you're not po-faced. I make sure all our pop songs follow a very strong line of thinking, otherwise they just become pap.

What do you represent in rock and roll?

One of the few genuine alternatives in a country where alternative is spelled with a capital "A." I do feel we stand on the sidelines from pretty much everything, heading in our own direction. There are certainly bands with a similar attitude, like EMF, Pop Will Eat Itself, and the Shamen, amongst others. My aim with the next album is to almost re-invent rock, to keep the lead that we have over people like, say, EMF, who by their own admission are influenced by us.

Isn't it strange that papers bill you as EMF's mentors but you'd never seen them perform live until you came to New York for press in April?

We had to appear very pal-y to the press because [they] wanted to create this huge riff between us. They would've had a field day with one nasty comment. If EMF ever actually slag us off in the paper I will just ignore it totally, because I know that they will have snapped. They're pushed every time someone does an interview with them to slag Jesus Jones off. People try to do it with me all the time. If I went into a club in London to see EMF it would be used as an excuse by those who like EMF, because they dislike Jesus Jones, as another way of getting at us. In a way, seeing them in New York for the first time was doing so on neutral territory, which is a good way of doing it.

You've stated that you don't believe in hero worship because you don't want to copy anyone's work. Is there someone, though, whose spirit you admire?

Jimi Hendrix. I don't think I would relate to him in any way whatsoever but his approach to playing the guitar was absolutely fascinating. Why did he distort all the rules of guitar playing so much? I'm sure what fascinates me is that I don't understand him. I understand not wanting to be like every other guitar player, but not the spirit of why he did it and the personality and especially the cosmic stuff that he was into. Joe Strummer comes across as being a very honest, down to earth person which is not easy to do and actually be that way is in fact a real shit. It's just another act that he's put on. I'm not saying that's true of him, I don't know, but his spirit is admirable whether that's the case or not.

Do you have any guilty pleasures?

Plenty because I'm not ashamed about them. Do you know "Without You" by Harry Nilsson? It's a wonderful tear jerker. I've actually just bought two Simon and Garfunkel albums. We have been known to attempt AC/DC songs in soundcheck. I've got a Dolly Parton tape at home which I love. She's got a lovely voice. How much deeper can I dig myself? I've sampled off a Status Quo record, possibly England's unhippest band ever.

Who is your favourite New Kid On The Block?

Oh, it's got to be Donnie. I have a story about this actually. Over a year ago, Smash Hits, the English pop paper, asked me "which music in the charts do you like and which don't you like." One band I didn't like was the New Kids, and I sort of put it in a vitriolic way. Two weeks later the New Kids turn up in England and Donnie saw this and was absolutely incensed by it. We actually get a fair bit of hate mail from the New Kids fans because of that. I read an interview about two months ago with him and he's obviously still hurting. I think he genuinely feels hurt rather than just dislikes me or hates the band. That really made me think, "This is no way to go through a life, to go around hurting people like that." I mean a year is a long time to still be smarting over that, but it was just a flippant comment.

Doubt is a pendulum swing from Liquidizer as you say, and you got the concept for it from being on the road. Now that you've written about life and being in a band, what's next?

I'm not sure really. I've started to think there are too many meaningful people in rock music, too many meaningful lyrics, it's a bit of a drag that everything has to mean something. It would be nice just to write songs that rhymed correctly that were just quite surreal like "I Am The Walrus." But there are always things to write about. If you go into any bookstore you find that out.

Review of Big In Alaska video - Record Collector - circa June 1991

I've always had a problem with Jesus Jones. Unlike, say, Pop Will Eat Itself, That Petrol Emotion or (early) Wonder Stuff, Jesus Jones lack that spark of originality, something to mark them out from the rest. All the ingredients were there from the start, but the whole business seemed a little forced, and too formularised. "Big In Alaska" charts Jesus Jones' progress from "Info Freako", their first, brash single released in demo form, to their latest amalgamation with dance rhythms, "Who? Where? Why?" and, at the very least, portrays the band as honest, down-to-earth good-time guys, courtesy of interview snippets between tracks filmed during their recent world-ish tour.

"Info Freako" somehow belies the flat 'miming in a plain studio' surroundings merely by using a moody, red backdrop; simple but relatively effective. The boring on-stage setting for "Never Enough" is alleviated only by a clever 'We're bigger than God' Beatles pastiche, with clips of newspaper headlines and the mass-burning of Jesus Jones vinyl (any takers?). Only when the band teamed up with John Maybury, for "Bring It On Down" do the promos start to liven up, utilising predictable yet effective, brightly-coloured mock-psychedlic efefcts. "Real Real Real" continues the pattern, Jesus Jones bedecked in garish acid-houise hooded tops. And only the large screen backdrop of clips from events in Eastern Europe distinguishes "Right Here Right Now", although the presence of a Happy Mondays Bez-style dance character is nothing short of plagiarism. But Jesus Jones' last two efforts bode well for the future. For "International Bright Young Thing", the group performed on a clear acrylic elevated stage above a blue floor, so that an assortment of backgrounds could then be added, giving the impression of the band performing in mid-air. And the video for "Who? Where? Why?" comes awash with colour filters, flowers and Monty Python graphics. "Big In Alaska" is far from being essential but hints that there's more to Jesus Jones than some, like myself, might have thought.

Review of Big In Alaska video - Q magazine - circa June 1991

This is one of those seven-clip, half-hour collections that strike while a

band is hot and leave behind a lingering odour of the punter being, if not burnt,

then mildy singed. Jesus Jones themselves are well to the forefront of the rock-dance

crossover, their designer urban guerilla chic not being the only thing to link

them back to The Clash, via of course, Big Audio Dynamite. Grandstanding three-minute

glories of streamlined raucousness is their bag, global calls-to-arms tempered

by the best graffitists' irrepressible sense of the ridiculous.

Linked mostly by the genial frontman Mike Edwards, these clips are padded out

with such cheery trivia as that the tinted contact lenses Mike had to wear for

Real Real Real didn't half give him gyp, and that when, in the £125 promo

for Info Freako, Mike energetically plunged his guitar groinwards in best axe

hero style, he not unsurprisingly found himself singing soprano and had to have

a tearful little lie down. The miracle is that staring upwards at the overhead

camera during International Bright Young Thing, he didn't complain of a cricked

neck.

Review of Big In Alaska video - Smash Hits- circa June 1991

Jesus Jones parade a galaxy of unfortunate fashion on this collection of all their greatest "hits". The video begins in their rather "ropey" early days and follows them through to the magnificence of Right Here Right Now and Who? Where? Why?. All the videos are kind of spewey, spinning, dizzy, whirly affairs where the camera won't stay still and the band loon about like flies in a jam jar. Sickly effects, top tunes and dishy fellas to boot, what a bloomin' bargain! (7 out of 10).

Review of Big In Alaska video - Select magazine - circa June 1991

Big In Alaska won't widen your eyes and mind to the misery and

grandeur of life, but it will tell you everything you need to know about

Jesus Jones' videos. Right...hoo-ray.

No, it's better than you might expect. Between the 'Info Freako's and

'Real Real Real's, Mike Edwards uses his talents as an interviewer and

home entertainment unit specialist to draw anecdotes and jokes from

his troops. Of 'Info Freako', Edwards recalls how he did himself an

injury while acting the rock star in the video. We look out for it and

it's there. Mike slamming his guitar down on his knee and reeling back

with the pain. It's great.

The videos are alright, but what makes them interesting is the light

cast on them by these interviews. Before 'Never Enough', bassist Al

Jaworski tells how they had to pay the screaming girls in the video

£90 each, for being screaming girls. He also talks of his hair

as: "Overbrushed, very little texture", and there it is -

overbrushed, with very little texture...

This is all very well for one viewing, but with visuals as ordinary

as those in 'Bring It On Down' and 'Real Real Real', it's hard to imagine

going back to it. Only 'International Bright Young Thing' hits the spot;

a disorientating travelogue that has the band hopping continents with

the aid of smart special effects.

'Right Here, Right Now' uses the horrible device of having the singer

watching TV and coming over all serious, (now there's something

you see every day).

'Never Enough' is a tame joke (the band claiming they're bigger than

The Beatles and having their records thrown into a pyre); 'Who? Where?

Why?' has a terrible title and unusually coloured flowers; 'Real Real

Real' displays the band as having a fucked dress-sense; and so on.

Overall, since it's affectionate, and doesn't make you feel like someone's

asking you to pick up the soap in the shower, Big In Alaska is

pleasant enough.

Walk, don't run to your nearest video emporium.

Review of Big In Alaska video - Probably from NME - circa June 1991

"No

one in the group is called Jesus...Their music you will find very different,"

announces Annie Nightingale to the heavily patronised Romanian crowd.

To us, however, Jesus Jones' mix'n'match music is far from unfamiliar.

With enough dayglo and grooves for the teenies and plenty of riffs and

sneers for the big boys, they're quintessentially last year's thing;

major label rock with a smattering of street cred.

'Big In Alaska' patches their seven not-enormously-dissimilar promos

together with the now obligatory and ever-tedious Super 8 footage of

'the lads' larking about on tour. Here they're revealed as unaffected,

inoffensive and deeply, deeply unfunny - a minute's worth of

pulling faces in wigs does not great comedy make.

Tellingly, the chronological trek through the videos shows Jesus Jones'

immaculately marketed progress to designer spontaneity. For the crackling,

still excellent debut 'Info Freako', black leather berets and a few

gauche, splayed-legs poses are modelled. By 'Real, Real, Real' they've

grown into headache-inducing hooded tops, coloured contact lenses and

frenetic instrument abuse. Finally, in 'Who? Where? Why?', they sit

contemplatively in a poppy field while Terry Gilliam-style animations

mouth the words behind them. With maturity comes a little self-conscious

weirdness, it seems.

'International Bright Young Thing' features the band zooming over shots

of planets, maps and stadia, to dizzying effect. Mainly, though, this

is repetitive, off-the-peg raucousness; EMF's embarrassingly 'zany'

uncles raised to global stardom. Still, if it sells...

Review of Big In Alaska video - Vox Magazine - July 1991

A shortish set (seven clips) that charts the Jones boys' metamorphosis from

surly skate brats to groomed chart heroes, Big In Alaska

captures the band's undeniable and raffish charm with deceptive

efficiency.

Linked with amateur home video footage shot during last year's

world tour, each promo shows marked progression from its predecessor.

The rather po-faced 'Info Freako' opens - plain, unadorned and

packed with shots of Mike Edwards, guitar at the hip, perfecting

the pout to which, whenever it's in doubt, the camera will return

for the next 30 minutes or so.

'Never Enough', is prefaced by the brazen admission that the

co-starring screaming female fans were paid £90 a day

for their services, shows the band at their wry best. 'Bring

It On Down' begins their fascination with blue-screen superimposition

and shows the band against a rain of fruit and veg, a technique

taken to new heights later in the absurd travelogue of 'International

Bright Young Thing'.

Self-parody comes furthest to the fore with 'Real Real Real'

and in such a frivolous context, the ensuing post-Romania promo

for 'Right Here, Right Now' jars somewhat. But it's a minor,

if sobering diversion. The final 'Who? Where? Why?' ends on

a triumphant, cod-classic note, mischeviously upstaged by shabby

tour footage that brings the package to a feeble, deliberately

anti-climactic close.

Bright as a button and big all over. Who can possibly resist

it?

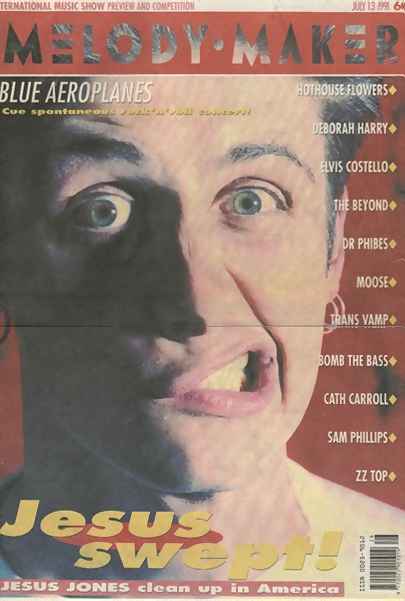

Interview - Melody Maker - 13th July 1991

Mike

Edwards is holding forth on his favourite subject: himself, with particular

emphasis on his ever-increasing proximity to rock'n'roll fame. There's

no stopping him.

"This is all brilliant. This is as much fun as you could ever possibly

have," he says. "And the fact that you get to visit places like Salt

Lake City, and you can grab some time early in the morning, and get out and

see the place...it's incredible."

I'm choosing to assume he means the concept rather than the reality. With the

exception of the two blocks of Mormon Disneyland called Temple Square, Salt

Lake City is everything but incredible, a drab prefab metropolis of wide streets,

spectacularly proportioned shopping malls and brightly-smiling people who look

like they were ironed fresh that morning. Nice mountains, though.

"Oh, come on," he admonishes, "it's when you come out here that

you can actually understand that whole 'Joshua Tree' thing, you can understand

why people do that . It looks so crap, back in England, when people do that

and this Americana overcomes them, but the thing with America is that there's

so much enthusiasm, so much exuberance. And it's such an incredible place, such

a momentous place. The scale of it, the physicality. Everything about it is

designed to impress you. No wonder the pioneers all went God-crazy."

Several hundred years later, the sons and daughters of the pioneers are going,

glibly enough, Jesus crazy. The Jones boy is rapidly becoming a star, and he

loves it.

Mike Edwards always said that one day he'd be famous, that one day his band

would take their energetic bastardisation of contemporary pop to the top of

the world's charts. For his troubles, he's generally received the sort of knowing

dismissiveness usually afforded six-year-old boys who've announced their intention

to become astronauts. But even as we sit in the restaurant of the labyrinthine

hotel with suites like funeral parlour waiting rooms and wonder what happened

to our coffee, Jesus Jones' second album, "Doubt", is in the Billboard

Top 30 with half a million sales under its belt, and the band's finest single

to date, "Right Here Right Now", is about to break the American Top

10.

Mike is stopped in streets from Tokyo to Sydney to Bucharest and every show

on this tour has sold out in advance. Mike, understandably, is in fine form.

"This is the real rock'n'roll mythology," he offers with an excited

David Attenborough shiver in his voice. "This is what the whole thing's

about. You get the incredible offers of sex, you get the screaming girls, you

get all the things you ever wanted and dreamed of the success in a rock'n'roll

band. It's all here. Everything."

Including the quick riches?

"Ah, well," He shrugs, "we're in the classic line of bands who

do not have the best deal in the world. Our manager is pretty irate about it,

and it probably does make us sound like idiots, but we just think, 'Hey, isn't

America great, royalties what are they, look at those mountains..."

Infectious though Mike's enthusiasm is, he's an odd one to be championing the

idea of life with "Hammer Of The Gods" as a guidebook. Mike has always

projected himself as the one who keeps his head while all around him are losing

theirs, as a man who somehow knows better than to indulge in such superficial

gratifications as sex, drugs and rock'n'roll.

So what kind of thrill do you get from standing back and behaving like you're

above it all?

"I find it incredibly good for the morale, "he grins, "to be

offered a blowjob after a show. But, to be quite honest, that kind of thing

doesn't impress me very much."

You're joking. I mean, isn't that the end result of everything you've ever wanted?

Aren't you having your cake and ignoring it?

"No," he states. "Well, frankly, all that stuff does become rather

embarrassing. You stand there after a gig, and someone comes backstage and says

there's these two beautiful women downstairs, they haven't got the proper passes,

they want to meet us an they're willing to...well, they want to blow the band.

And you think...can you actuallty imagine yourself walking downstairs, taking

your trousers down and saying, 'Okay, go...' It's just rock'n'roll for the sake

of it. I wouldn't do it."

But, surely, unless you're the sort who leaves straight after the show to go

and give the halo a spit-polish, you'd have to be more than human not to have

dipped your toe in the water, so to speak...

"Oh, yeah, absolutely. And certain members of the band have tried it on

a number of occasions. But we've been going two and a half years now.

We've done it all.

"And this," he smiles, waving a teaspoon and warming to his point,

"this is nothing compared to Japan. Japan is obscene for that. There

are so many women there who want to be with a band, and there's a very well-organised

groupie system there as well. Here, it's pretty chaotic, and people do it on

the spur of the moment. Over there, it's very regimented."

What, like take a number and wait?

"Almost. In fact, if you instigated a sytem like that, they wouldn't think

anything wrong with it."

In the state of Utah, marital polygamy is entirely legal, if frowned upon in

polite circles. Oral sex carries a gaol sentence. Mike loves contradictions,

and this is one of his particular favourites.

"It's just so..." he stops. He giggles. "I love America,"

he says.

Saint Mike The Chaste And Sensible tells me about the books on American history

he's reading at the moment, how great mountain cycling in Utah is and about

his faintly monkish attitude to the trials of touring, as if that which doesn't

kill him makes him stronger. I start wondering if he's in the wrong job.

So where's the fascination in spending long hours in a bus with people who sweat

and fart and get irritating, then. Why tour?

"Pecan pie," smiles Mike as his long-presumed missing-in-action dessert

arrives. The elderly waitress has an accent you could sharpen an axe on and

regards us and our hair and my tape recorder with equal parts suspicion and

curiosity.

"Are you with some kind of band?" she grizzles.

"Er, yes," says Mike, hoping that the inevitable response to the inevitable

next question won't get him railroaded out of town in a tar-and-feather suit.

"What's the band?"

"The name of the band is, um...Jesus Jones." He winces.

"I see," she says, shooting me a further disapproving look, when I

accidently take the Saviour's name in vain as a strawberry pie the size and

shape of one of the Queen's Ascot hats arrives on the table.

"I did tell you you wouldn't regret ordering it," she says, and stomps

off. The pie is truly great, if you're ever passing that way.

"Sorry, where were we? Oh yeah. The continued fascination is the constantly

changing scenery, the fact that we're getting more and more famous all the time

which, as you know, has always been very high on my list of priorities,"

Mike says without drawing breath. "And those things in themselves are almost

enough. But also, just the actual being in a rock band and being able to do

all these things. For me, that's what it's all about. I've been obsessed with

fame, with rock bands and with fame since I was about five years old."

Another perennial source of inspiration is the varying nature of projectiles

hurled from the audience.

"We've had all the usual things, the socks and underwear and stuff but

somewhere, I can't remember where, they threw sheeps' hearts," Mike explains.

"We don't know why. Perhaps to keep the roadies amused. It certainly amused

us, anyway, seeing this roadie run across stage, pick up this heart and go,

'Huuuurrrrgggghhhh'..."

A few months back, in a Not Terribly Interesting Rock Monthly near you, Jesus

Jones' dervish keyboardist Iain brightened up an otherwise resoundingly drab

story by offering the opinion that the songs Mike writes reflect rather too

much the austerity of the author, that they "lack humanity". Even

more surprisingly, this was a view readily supported by the rest of the band.

"Um," ponders Mike between mouthfuls, "I remember that. I considered

all their comments...and considered firing them all, ha ha. But the rest of

the band are very astute when it comes to assessing me, because they spend all

their time with me. They know me inside out. And I think Iain's right. I would

agree with but I think what I do is struggle against that all the time, and

that's the point at which what I make is what I make."

Do you feel in any way that you try too hard? Do you find yourself having to

justify everything you write to yourself?

"Mmm-hmm, yeah. It's the thing that takes the longest about my lyrics.

It's not making them rhyme or anything, it's looking at each line and wondering

if each line is worth anything. Also, every line I have to think, 'Is this proper

English?'. That's one of my classic bits of stupidity."

Perhaps unaware that he has just raised himself several dozen notches in the

estimation of his interrogator, Mike proceeds to fluff around the point for

fear of sounding like a complete anal-retentive grammatical obsessive until

he's reassured that wanting to bring back public hanging for perpetrators of

floating apostrophes is an entirely reasonable thing.

"Yeah?" he asks. "Oh good, I should introduce you to the rest

of the band. They could hate both of us then. That's another thing about being

in America, you start getting incredibly pedantic about the state of the English

language. Like, what does 'the alternate version' mean? And people do

not get 'oriented'."

Rarin'!

To say that Jesus Jones have their detractors is akin to observing that the

state of Utah has some peculiar laws about relations between consenting adults.

The press honeymoon that followed the release of the mighty "Info Freako"

back in '89 was short, very short, definitely of the whip-it-in-whip-it-out-wipe-it-put-it-away

variety, and ever since then, so many people have managed to develop such a

pathological dislike for the band, it's almost enough to make one start liking

them just for the sheer contrary hell of it.

Jesus Jones stand accused of many things, most frequently of peddling an antiseptic,

androidal music that provides a swift, efficient pop high without leaving so

much as a nagging aftertaste; of being calculating careerists fronted by a ruthless

egotist with more mouth than trousers; of being guilty of pretty much everything

up to and including the murder of Rasputin and the Lindbergh kidnap.

The

case for the defence, however, would feel compelled to observe that there

are certainly worse things that could be in the US Top 10 than "Right

Here Right Now" (an abrasively produced lament to hopes raised and

shattered by the collapse of communism, as it happens), that a man of

Mike Edward's intelligence and honesty can't be all bad an entity to have

around, that Jesus Jones remain, on their night one of the best live bands

on the planet, and that whatever happens, they've got way, way more charisma

than any of the legion dullards who leapt on the dance/rock bandwagon

that the DIY landmark "Info Freako" helped (just as much as

"W.F.L." or "Fool's Gold") assemble. Yeah, and

they've written more than one song, too.

The

case for the defence, however, would feel compelled to observe that there

are certainly worse things that could be in the US Top 10 than "Right

Here Right Now" (an abrasively produced lament to hopes raised and

shattered by the collapse of communism, as it happens), that a man of

Mike Edward's intelligence and honesty can't be all bad an entity to have

around, that Jesus Jones remain, on their night one of the best live bands

on the planet, and that whatever happens, they've got way, way more charisma

than any of the legion dullards who leapt on the dance/rock bandwagon

that the DIY landmark "Info Freako" helped (just as much as

"W.F.L." or "Fool's Gold") assemble. Yeah, and

they've written more than one song, too.

So, Mike, what will the Jesus Jones album of the future sound like? Be bursting

with long-stifled humanity, will it?

"Well, see, practically all of 'Doubt' was me trying to put some humanity

back into things after 'Liquidizer' which was well, you know, very one-dimensional.

Maybe it's some sort of stupid quest for artistry, but I definitely want some

of me in my records."

Do you suffer from that old thing of not wanting to give too much away?

"Yeah. That's one of my main obsessions, one of my main fears. I am actually

a very private person, so it's a very strange position to be in, having to talk

about it."

Miek Edwards licks at the remnants of his pie and enthuses at me about Middle

Eastern folk music, hardcore techno House, Throwing Muses, 808 State, Naplam

Death, Jane's Addiction and John Zorn while I boggle quietly at the idea of

the sum of those influences, Mike's magpie ear for samples and the next Jesus

Jones album. I tell Mike that during his absence in America, his band have been

singled out for their debut in Mr Abusing's column and he smiles and says it's

about time. I wonder if Mike was at all perturbed by the Tailcoat-grabbing success

of the (actually rather brilliant) EMF.

"No," he says, "not at all. I think everyone imagined there would

be this huge rift between us, and the press tried to create this huge battle,

which is probably why we became so sickeningly friendly in print. I think there's

a lot of potential there for a very good band. And I'll be the first to rip

them off the minute they do something great."

Outside, the sun is setting over the mountains, and the sight launches Mike

into another of his extended eulogies to America's geography.

Would you ever do a "Joshua Tree" yourself and write about all this?

"God, no. It wouldn't interest me in the slightest, because I think it

would exclude people. I might perhaps write about how, if you were here, you

would feel about it, but not 'Route 66', no. I mean, people in Warsaw look at

those sort of lyrics and think, 'This means sod all to me', and quite right,

I've done that too. It's pointless to write songs that exclude people."

Acting locally, thinking globally, Jesus Jones are a miracle of ambition. And

a great pop band.

Review of Right Here Right Now Re-release - Probably from NME - circa July 1991

While I'd like to congratulate Jesus Jones on their US success, and give them kudos for being political with a small 'p', this re-release isn't as gripping as Mike Edward' haircut.

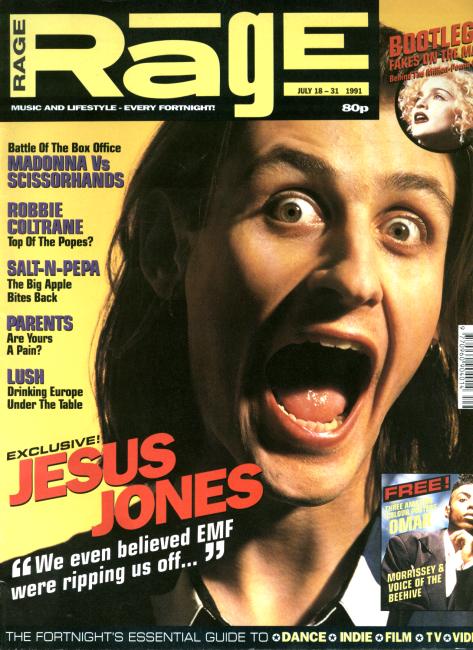

Interview - Rage Magazine - 18th July 1991

Next time you're in London and nearly knocked off your feet by a gas-masked cycle courier stop and check him out.

If you see a Rage shoulder-bag retreating into the distance then you've just escaped being decked by Mike Edwards, the "Unashamed egotist" and charming meglomaniac behind the sample-trampling cyclone that is Jesus Jones.

"Oh yes, I've done well by Rage," he grins as he relaxes, chunky blue Filas extended, in EMI Records' offices. He's a fast talker, articulate and engaging, and it's instantly apparent that his electric enthusiasm for all things Jesus Jones is undimmed by their recently concluded five month world tour.

"Those Rage backpacks are briliiant," he continues. "I bike around London a lot nowadays, and it's been a Godsend. A Ragesend, in fact."

Stop grovelling, man.

"Heh heh... Well, I had to give up the Tube, because it got a little painful. It was either me saying, Yes, thank you, I already know the words to 'Who? Where? Why?'. Or people going, Look, it's Jesus!

"And they think it's funny. I mean, you'd expect it in America, but we got it in Australia too. Airline stewardesses asking, So which one's Jesus then?"

Ah, fame - it's a bugger, isn't it? Still, Mike and the rest of the Jones can't say they weren't asking for it.

Their rabid buzzsaw classic of dance-thrash fusion 'Info Freako' just stalled on the lip of the charts in February 1989. But it was still unsurpassed 18 months later when everyone had realised that Jesus Jones, Age Of Chance and Big Audio Dynamite had been right all along - it was a very good idea to spot-weld the funky drummer to the spunky strummer.

And by then Jesus Jones were off on another different planet , finally uniting all those disparate people they'd rashly namechecked on their debut LP 'Liquidizer' (Big Black, the Turntable Orchestra, Napalm Death, Public Enemy and so on) into the deafening number one pop frenzy of 'Doubt'.

They even joined a select group that includes Morrissey, Cliff Richard, U2 and the bloke that wrote the Star Trek theme earlier this year, when Britain's top light entertainer and newsagent, Vic Reeves opened one of his Big Nights Out with the faithful version of 'International Bright Young Thing' ("My crowning moment!" quips Mike, 26). No wonder air hostesses get uppity with them.

Times are strange, though. With a pop life just three years old, Jesus Jones - the band who, more than anyone, fulfil the old cliché about 'music you can't pigeonhole' - find themselves credited as godfathers to a scene-that-never-was. Every band with an Akai sampler and a feedback pedal is now accused of taking the Jesus Jones challenge.

"And of course they're all better than us," Mike observes with mild testiness.

"No... I will pass comment on any band whatsoever but I don't feel we've fathered anything."

Some people reckon you fathered EMF.

"Ah... the whole comparison thing about EMF is sad, but the saddest thing about it is that everyone believed it," Mike sighs.

"To a certain extent, when people around you are saying, This band EMF are really successful and they've ripped you off - you start to slightly believe it yourself... which shows that I'm not that intelligent most of the time!

Because it isn't true, because I've seen EMF and there's a world of difference between the two bands. As much as there is between us and the Happy Mondays," he emphasises.

"But what we both did when those things were being written about us became sickly.

"We were not gonna let anyone stir the shit between us, we became repulsively friendly! We made an effort to get so close together that people couldn't tear us apart.

"Look, I went to see EMF live in New York - not wanting to see them in England with all the stupid bitchiness - and my honest feeling about them now is that there were elements which were great. The potential for an excellent band is there. But there is a big difference between the two bands.

"The reason Jesus Jones sounds the way we sound is because of The Shamen - they were the ones," he states.

"I saw them at Notre Dame Hall in Leicester Square in '87, '88 or something. And I set up a band that way, by ripping off The Shamen. But I got it wrong, and the way I got it wrong was important. That made the difference."

The difference is now making itself felt in America. Of all the new British bands, only Jesus Jones and EMF have made a serious impact on America's mainstream pop charts. 'Doubt' is going Top 20, and 'Right Here, Right Now' - which is out again here this week - could easily be the number one there by the time you read this.

But though Mike wrote the song as a snap response to the fall of communism at the end of '89, some Amerians have shanghai'd it, and particularly its chorus - 'Right here right now/There is no other place I would rather be' - as a soundtrack to the ugly orgy of national self-congratulation following their crushing victory in the Gulf War.

Jesus Jones toured America in the aftermath of the War - how would Mike feel if he'd unwittingly written the anthem for a hollow victory? The Jesus Jones svengali's reply is a cagey one.

"For better or worse people reinterpret pop music for their own uses," he argues.

"I know that people are doing what they want with my music - but that's important. I want them to. When I wrote that song, I was trying to get a feeling of optimism, a feel for the times. The end of the '80s was a fantastic time to be alive and the world really did look like it was changing for the better.

"Very naive, I agree," he concedes.

"But then there was an American TV programme that showed US troops landing in the Gulf to the sound of 'Right Here, Right Now', as a kind of advert for the Gulf War.

"Now I didn't like that at all, and I said so at our gigs in America. But what I did notice, which makes me feel not quite so bad about the whole thing, is that for Americans, not repeating the Vietnam experience was a great feeling. And 'Right Here, Right Now' hit a time of immense optimism, of burgeoning self-confidence for them.

"I had one specific incident on that tour of a girl who came up to me after a gig. And she said, I've got some friends who were over in Saudi Arabia during the war, and I was really scared for them. And that song gave me a great deal of optimism, it made be feel happier.

"For most people I don't believe that lyrics in rock music matter a damn, but if 'Right Here, Right Now' makes people feel good - and the Americans I spoke to weren't the ones who went and murdered people - or they see it as bringing them confidence and optimism then that's not a bad achievement."

"For most people I don't believe that lyrics in rock music matter a damn, but if 'Right Here, Right Now' makes people feel good - and the Americans I spoke to weren't the ones who went and murdered people - or they see it as bringing them confidence and optimism then that's not a bad achievement."

This is the kind of thinking that has earned Jesus Jones no end of stick from the pundits, many of whom think the band - and Mike in particular - are too clever for their own good.

"We do get criticised for being intelligent and good-looking," Mike smiles modestly. "Those are two cardinal sins. It is better to be ugly and stupid in rock music.

"But the big slap in the face for me was 'Real, Real, Real'," he recalls, of the single which caused a horrendous kerfuffle among the purists. One, because it was mixed by one of Pete Waterman's PWL people, Phil Harding, and two, because it had the cheek to be 100 per cent diamond-studded pop (and a hit) into the bargain.

"I thought it was quite sarcastic and ironic, us singing about how crap pop lyrics are in the middle of the Top 20, surrounded by crap lyrics." Mike muses.

"But everyone went, Ha ha, here's more crap pop lyrics by that crap pop band Jesus Jones! So I thought, that's how much attention people pay.

"To an extent, we've even asked for trouble, for instance with a single that's a load of dogshit like 'Who? Where? Why?'" he continues, blithely destroying the illusions of a legion of Jesus Jones fans.

"We dug our own grave on that one. It's only redeemable quality was that it had a B-Side, 'Caricature', which is one of the best moments of our live show."

Why does he hate it so much?

"Because it's not what I thought it was when I first heard it... No that's not a good a answer. The fact is that our other singles weren't bland, they had a point to them, they had little edges to them and they knew what they were trying to achieve. There is something unnerving about them. One of the problems with the idea of 'Doubt' is that it can verge on self-pity, and 'Who? Where? Why?' crosses that line a little too often."

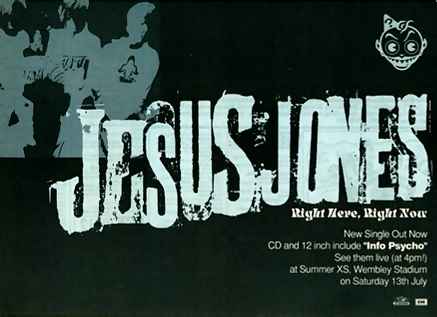

Jesus Jones were due to play their biggest show yet on July 13, when they would inject some much-needed buzz into INXS' mega pub-rock gig at Wembley Stadium. Then it's a heavy summer of European festivals, and intensive recording on their next LP.

Mike says that he's got a 'a concept' for it. Sounds horrible.

"I don't want the next one to be as diverse as 'Doubt'. I want more of a unified approach, an overall look - a direction. But there's nothing wrong with making a concept album for the '90s as long as it isn't a concept album for the '70s."

So is this goodbye to the sound that earned them the peculiar tag of 'Post-modern metal'?

"Ha ha! Yes! That was The Washington Post! Their concert reviewer called us, A heavy metal band with more than headbanging on its mind! Wonderful!

"But it was a bad night. We've never played well in Washington."

He shrugs.

"And on our bad nights we probably are a heavy metal band..."